I’ve heard farmers have to buy new plant seeds every year. Why can’t they save and re-use their seeds instead?

Farmers do have a choice and any requirement to buy seed (organic, conventional, or genetically modified varieties) each year can arise from equipment requirements, planting choice, biological and/or contractual reasons.

Many farmers chose not to save seed from year to year to plant, whether they farm organically, conventionally or using genetically modified seeds, and there are many reasons for this.

One of the reasons that farmers choose not to save seeds from year to year is because they need special equipment to clean the seeds to get them ready to plant, and extra storage space to store the seeds from harvest until it is time to plant again. Not all farmers have this equipment or the storage space.

Another reason is that many farmers choose the improved yields and crop vigour offered by hybrid seed varieties. Hybrid seed varieties, such as some corn and sorghum varieties, have been around for many years, since the 1930s in some instances, and can be produced through both conventional (classical) breeding and modern breeding methods using biotechnology techniques and are permitted in organic agriculture. Hybrids are made by crossing two highly inbred ‘parent’ plants. First generation hybrids, however, do not breed true to type, meaning that the seed they set may not grow into crops that are identical to the ‘parent’ plants. This can result in variations in yield and quality therefore many farmers prefer to buy new hybrid seed each year to ensure consistency in their final product.

A further reason that farmers do not save seeds to plant is that they may not want to plant the same variety again. Purchasing seeds every year means that farmers can choose a different crop to plant (canola instead of legumes, or barley instead of wheat), or they can simply plant an improved variety of the same crop.

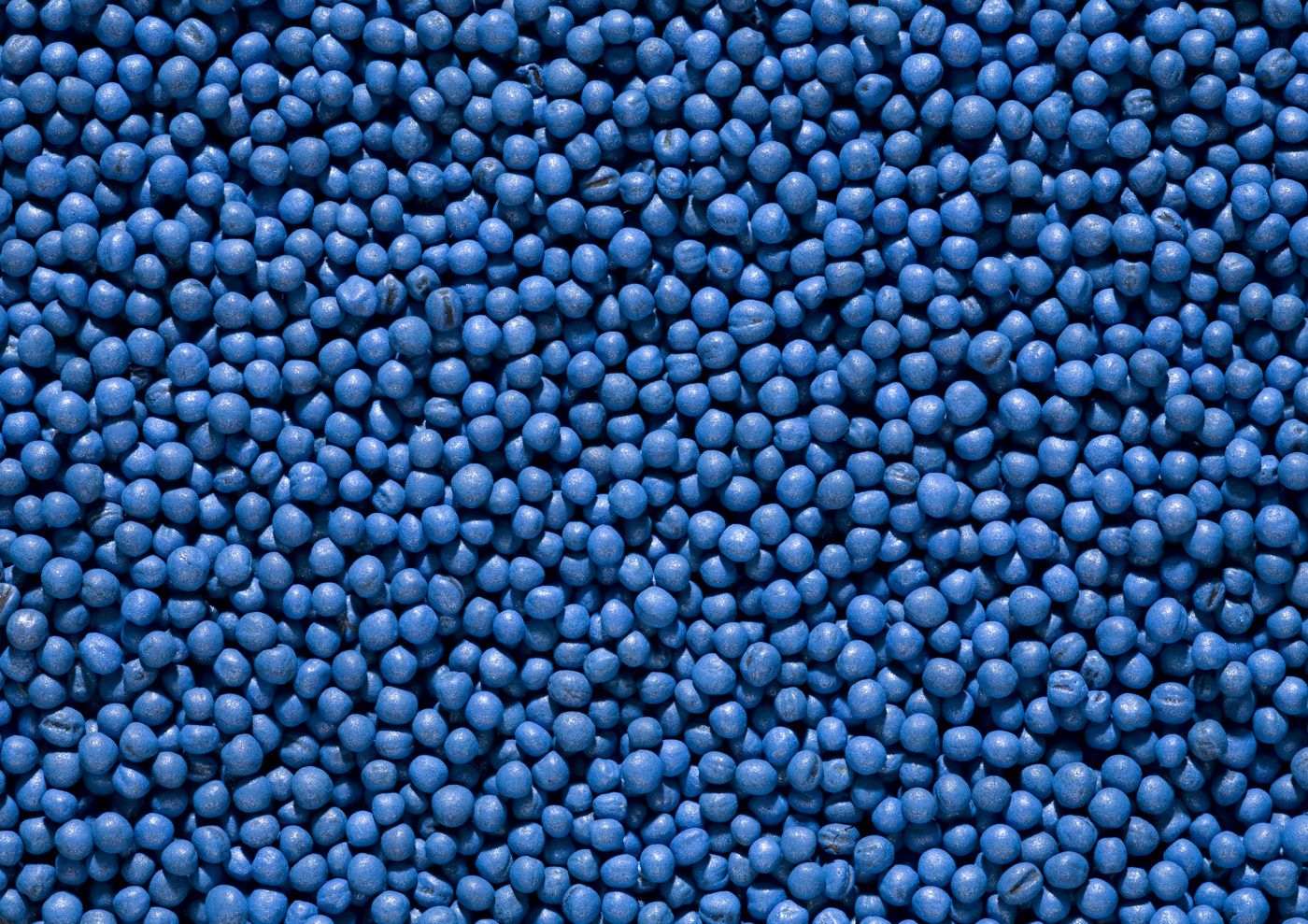

Farmers may also choose to purchase new seed every year, rather than saving their seed, so they can purchase seed that has been pre-treated with an insecticide or fungicide. Pre-treatments will help protect growing seeds against pests and diseases that live in soils.

Plant breeders (whether individuals, companies, cooperatives or universities) invest heavily in creating, developing and testing new varieties of crops. Intellectual Property provides the ‘exclusive Right’ that allows the plant breeder to have a chance to recover those costs if seed dealers and farmer adopt that variety and pay for the seed. There are hundreds of companies, cooperatives, individuals and universities around the world that sell seeds to farmers. Just as the home gardener has the choice of what seeds to purchase from their favourite garden store, farmers have the choice of what to buy from their favourite seed organisation.

Conventional seeds can have IP protection, as can organic crops, ornamental plants and GM crops. In most countries, growers who choose to grow GM crops enter into an agreement with the technology providers to buy new seed each year. As well as the agronomic advantages this provides, these contracts are vital for funding on-going research and development. It takes around 13 years and costs US $136 million to bring a new GM crop to market, most of which goes towards gathering the data required by the regulatory system in every country they are made available. This scale of private investment would simply not occur without the opportunity for commercial return provided by these contracts with growers.

Farmers quite easily calculate whether the costs of improved seeds is worthwhile to them. The choice of seed is based upon the best variety suitable for the conditions on the farm. Farmers would be reluctant to enter into contracts unless the technology was providing proven long-term benefits. There has been continued and rapid growth in the adoption of GM crops around the world, with the latest figures showing 18 million farmers were growing them in 2016.